CONTENTS

Volume 10 No.2 Fall 2021

- Demystifying Spelling:

Words Have Internal Structures

by Sue Scibetta Hegland - New Infographic! – Structured Literacy: Grounded in the Science of Reading

- Dyslexia-Specific Font: A Promised Solution But Is It Effective?By Pamela R. Shewalter & Timothy N. Odegard

- Implementation Is Like Instruction

By Nancy Chapel Eberhardt - Remembering Regina Boulware-Gooden

Editorial Team

Chief Executive Officer: Sonja Banks

Executive Editor-in-Chief: Carolyn D. Cowen, Ed.M., CDT

Editor-in-Chief: Nancy Cushen White, Ed.D., CDT, CALT-QI, BCET

Director of Publications/Resources: Denise Douce

Managing Editor: Candace Stuart

Content Editors:

Elsa Cárdenas-Hagan, Ph.D.

Georgette Dickman, M.A., OG-ThT, CDT

Nancy Chapel Eberhardt

Terri Hessler, Ph.D.

Theresa Kaska

Board Executive Committee:

Josh Clark, Chair

Jennifer Topple, M.S., CCC/SLP, Immediate Past Chair

Paul Carbonneau, Vice Chair

Mary Wennersten, M.Ed., Vice Chair

Dean Conklin, Ed.D., Treasurer

Courtney Gilstrap LeVinus, Secretary

Janet Thibeau, Branch Council Chair

Board Members-at-Large:

Stephanie Al Otaiba, Ph.D.

Dean Bragonier

Don Compton, Ph.D.

Carolyn D. Cowen, Ed.M.

Gad Elbeheri, Ph.D.

Angus Haig

Robert Lane, Ed.D.

Joanna Price

Elizabeth Woody Remington, M.Ed.

Shawn Anthony Robinson, Ph.D.

Scientific Advisory Board:

Elena Grigorenko, Ph.D., Chair

Members:

Elsje van Bergen, Ph.D.

Laurie E. Cutting, Ph.D.

Holly Fitch, Ph.D.

Lynn Fuchs, Ph.D.

Sara Hart, Ph.D.

Fumiko Hoeft, M.D., Ph.D.

Charles Hulme, Ph.D.

Nicole Landi, Ph.D.

Catherine McBride, Ph.D.

Julie Washington, Ph.D.

Jason Yeatman, Ph.D.

To provide feedback or request advertising space,

please contact info@DyslexiaIDA.org

Copyright © 2021 International Dyslexia Association (IDA). Opinions expressed in

The Examiner and/or via links do not necessarily reflect those of IDA.

Demystifying Spelling:

Words Have Internal Structures

Key Takeaways

- Words in English, including so-called irregular words like says, been, and does, follow a consistent, logical spelling process.

- Teaching the structure of words (morphology) and the conventions for combining morphemic elements from the very beginning prepares students to understand our spelling system.

- Students with dyslexia do not need to memorize these words; once they understand their structures and the consistent processes that form them, they can construct them as needed.

Students with dyslexia often struggle with spelling, particularly with so-called irregular words—words like says, been, and does. Typically, these words are viewed as rule-breakers because their spelling and pronunciation do not seem to match. They are thought to have tricky parts that must be memorized. This rote learning is seen as a necessary supplement to the explicit instruction and practice that occurs in Structured Literacy approaches.

However, these words do not need to be memorized; they follow the same spelling conventions as other words in English. In this article, we will see how structural analysis (morphology) allows us to understand them. This type of analysis reveals integral aspects of spelling that should be part of systematic instruction from the beginning.

Do Some Words Have Irregular Spellings?

Many words commonly described as irregular are not irregular at all; they are simply misunderstood. To understand them, we must recognize their internal structures—their morphology. There is growing awareness that morphology is a critically important aspect of literacy. However, in an effort to make the learning process more manageable for students, especially those with dyslexia, morphology is often ignored in the early years of instruction. Unfortunately, the learning process does not become easier for anyone when we attempt to steer clear of morphology.

When we disregard the structure of words like says, been, and does, we miss the fact that they are all complex—composed of more than one written morphological element or structural unit.

If we stop to think about it, we see this immediately in the word says, which is spelled by combining the elements <say> and <-s>. (In this article, angle brackets < > are used to refer to a written, spelled form of a word. For example, <says> refers to the written word spelled S AY S.) The structural analysis of <says> can be shown using an algorithm from orthographic linguistics—a word sum: <says ➞ say + s>.

Given this analysis, can we call the spelling <says> irregular? Compare how these words are spelled:

I walk; he walks: <walk + s ➞ walks>

I run; he runs: <run + s ➞ runs>

You play; she plays: <play + s ➞ plays>

You say; she says: <say + s ➞ says>

The structural pattern in all these present-tense third-person singular verbs is the same. And the same pattern is found in the spelling of the words goes and does, which are formed from the base elements <go> and <do> combined with the suffix <-es>. An <-es> is a form of the suffix <-s> that is used in specific situations. Traditionally, one of those situations is when this suffix follows a word ending in a single <o>.

They echo; it echoes: <echo + es ➞ echoes>

We go; he goes: <go + es ➞ goes>

You do; she does: <do + es ➞ does>

In all seven of these word sums, we see a consistent, logical process for combining written elements. Yet only says, does (and sometimes goes) are described as “rule breakers.” Why is this? Although the pronunciation of says and does may be unexpected, their spellings are coherent.

We find the same structural coherence in the written word <been>, which is spelled by combining the base element <be> and the suffix <-en>: <be + en ➞ been>. This past participle suffix <-en> is found in the spelling of several common verbs.

I will eat; I have eaten: <eat + en ➞ eaten>

I will give; I have given: <give/ + en ➞ given>

I will drive; I have driven: <drive/ + en ➞ driven>

I will be; I have been: <be + en ➞ been>

In the word sums above, you see the replacement of the final, unpronounced <e> at the end of the base elements <drive> and <give>. (A forward slash in a word sum is a signal of that replacement process.)

This replacement of an <e> occurs when we add <-en>, which is a vowel suffix: one that begins with a vowel letter. This is the “E Convention” at work—a consistent suffixing pattern that will be familiar to Structured Literacy practitioners.

You may wonder why the <e> at the end of <be> is not replaced when the vowel suffix <-en> is added. That <e> remains part of the spelling because it is representing the final segment of pronunciation in the spoken word be. A final <e> that is pronounced is not replaced during suffixing. When writing been, we simply add the suffix to the base. We see the same pattern when writing the word being:

be + en ➞ been

be + ing ➞ being

Once we identify the structural elements in the written word <been> and notice the consistent suffixing conventions at work, its spelling—just like <says>, <does>, and <goes>—is perfectly logical. If we continue to have doubts about these words, perhaps we should reexamine our assumptions about English spelling.

Morphology Matters More Than We May Think

The spelling of an English word is not necessarily the most direct representation of its pronunciation, because spelling integrates information about two aspects of language: morphemes and phonemes. The fact that phonemes are represented in written language is widely recognized. We know that graphemes (letters or combination of letters like the <f>, <i>, and <sh> in <fish>) represent phonemes, which we can think of as the distinctive segments of pronunciation in spoken words.

What we often miss, however, is the fact that many words cannot be successfully spelled by simply laying down a series of graphemes to represent the phonemes in our particular pronunciation of the spoken word. Although those phoneme-grapheme relationships are clearly important, when we look deeper, we find that there is more going on. Written words are formed by a systematic synthesis of written morphemes—the structural elements that come together to create words. We see this in the words we have been discussing, where elements have come together in a logical way to form spelled words: says is written by combining the base <say> and suffix <-s>, been is spelled with <be> and <-en>, and does and goes are spelled with the base elements <do>, <go>, and the suffix <-es>.

Although the relationships between spelling and pronunciation in these words may surprise us, there is nothing irregular about their spelling. In fact, they reveal an essential, foundational concept of English spelling.

Consistent Spelling of Morphological Elements

The pronunciation differences that we notice in do/does, say/says, and be/been are not unique. Such shifts in pronunciation frequently occur as prefixes and suffixes are added to and removed from words. Think about finite/infinity, labor/collaborate, grade/gradual, probe/probable. Notice the consistent spelling of the structural elements shared by these written words, even though their pronunciations change. Flexible grapheme-phoneme relationships allow for the consistent spelling of written morphemic elements.

It Is Time to Rethink Our Expectations about Spelling

Pervasive frustration with so-called irregular words is the result of inherited, unquestioned expectations and beliefs about how our orthographic (spelling) system works and how it should be presented to students.

Without a doubt, explicit instruction in phoneme-grapheme and grapheme-phoneme relationships is essential for early learners. For those relationships to make sense across the entire system, however, students must understand that the internal structures of words provide the framework for spelling. We can help them see this by showing them the structures of common, logically spelled words like does, goes, been, and says. Students with dyslexia do not need to memorize these words. Once they understand the spelling of the written elements within these words and the consistent processes that occur as we combine those elements, they can construct these spellings as needed.

As collaborators who are committed to helping all students succeed, we must begin to ask how we can incorporate an understanding of morphology into literacy instruction from the very beginning. Although most systematic instruction starts by focusing on phoneme-grapheme relationships in isolation, students cannot make sense of those relationships without considering morphology, the influences of etymology, orthographic conventions, and other factors.

Liberated from the notion that does, been, says and goes are irregularly spelled, we can use these logically spelled words as an illustration of the importance of structural elements in words. Rather than being a source of confusion and frustration, these no-longer-irregular words can be a point of entry for studying the coherence of English spelling.

Selected Morphological Terminology

- Morpheme: A structural component of a written or spoken word. A morpheme works as a unit to contribute to the overall meaning of a word and cannot be divided without losing that contribution.

- Element: The written form of a morpheme.

- Base element: The foundation of a written word. Carries a distinctive, general kernel of “meaning.” Every English word contains at least one base element.

- Affix: Affects or modifies the meaning of a base it is attached to.

- Prefix: An affix that precedes a base.

- Suffix: An affix that follows a base.

Sue Scibetta Hegland is an author and frequent speaker on topics related to spelling. She provides information to support explicit, systematic instruction in written English, including the importance of morphology and the influences of etymology. Her early professional experience was in experimental research and instructional design, but her focus shifted in 2003 when she learned that one of her children is dyslexic. Trained in the Orton-Gillingham approach, she has served on the Board of Directors for the Upper Midwest Branch of the International Dyslexia Association, and on the Board of Education for the Brandon Valley School District. She is currently Editor-in-Chief for the International Dyslexia Association’s Fact Sheet publications and is the author of the website LearningAboutSpelling.com. Her new book on spelling will be released this fall.

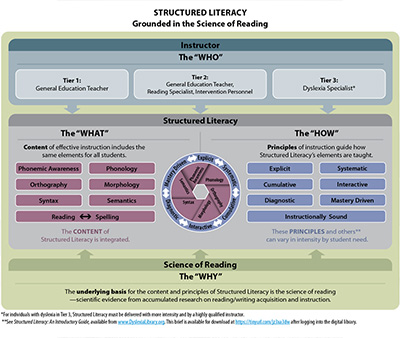

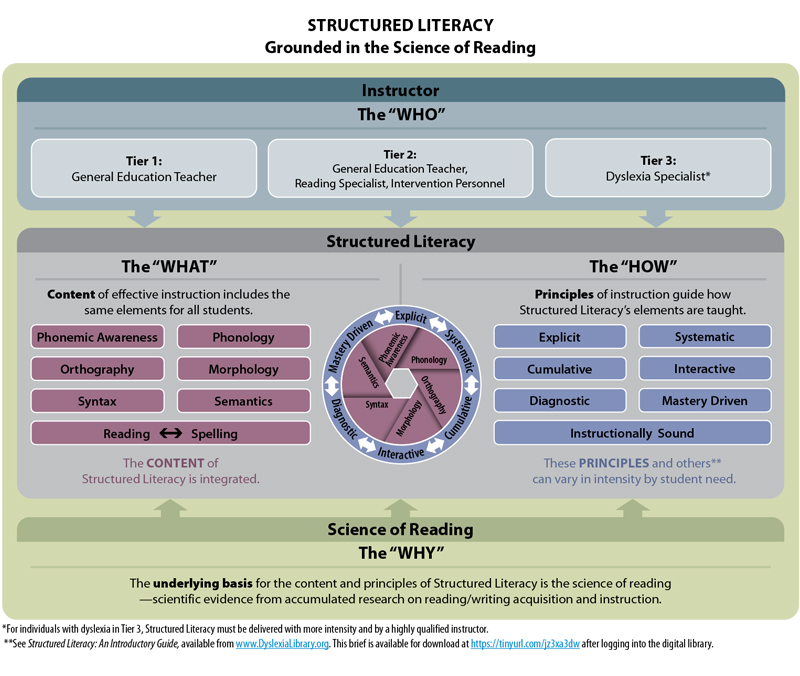

New Infographic!

Structured Literacy Grounded in the Science of Reading

Structured Literacy teaching is the most effective approach for students who experience unusual difficulty learning to read and spell printed words. The term refers to both the content (the What) and methods or principles of instruction (the How).

Structured Literacy teaching stands in contrast with approaches that are popular in many schools but that do not teach oral and written language skills in an explicit, systematic manner. Evidence (the Why) is strong that the majority of students learn to read better with structured teaching of basic language skills, and that the components and methods of Structured Literacy are critical for students with reading disabilities including dyslexia. (See IDA’s fact sheet “Structured Literacy: Effective Instruction for Students with Dyslexia and Related Reading Difficulties” for more information.)

The International Dyslexia Association (IDA) is grateful to IDA’s Fact Sheet Editorial Board and Structured Literacy Task Force and the Communications and Graphics Teams at Wilson Language Training who collaborated to create this infographic. You can download a copy from the Dyslexia Digital Library at DyslexiaLibrary.org.

Dyslexia-Specific Font:

A Promised Solution but Is It Effective?

Key Takeaways

- Dyslexia-specific fonts are an outgrowth of theories of dyslexia that are not widely accepted today.

- There is little evidence to support the use of dyslexia-specific fonts as tools to help students with dyslexia read better.

- Investing time and money into dyslexia-specific fonts potentially diverts resources from effective and affordable evidence-based accommodations and materials.

Dyslexia is characterized by difficulties accurately and fluently reading words and spelling. Today the most widely accepted theory is that people with dyslexia have problems processing sounds within words and connecting these sounds to letters. But other theories have been proposed over the years, with the most popular focusing on vision. One of the most common has been that people with dyslexia do not see letters as typical readers do. Instead, the letters might appear reversed or move around when they attempt to read. At one point, some people with dyslexia were given colored overlays or glasses with tinted lenses to remediate the problem, an approach whose effectiveness has been disproven by research. (For a detailed review of this approach, please read the article “Behavioral Optometry and Irlen Lenses to Resolve Reading Problems” in the Winter 2020 issue of Perspectives on Language and Literacy.)

Based on visual theories of dyslexia, dyslexia-specific fonts have emerged as a potential tool to help students with dyslexia read better. Parents and educators often ask us about these fonts and how well they work.

Here are the most common questions we receive:

- Why might dyslexia-specific fonts matter?

- What features of dyslexia-specific fonts make them different from other fonts?

- Are dyslexia-specific fonts an effective accommodation for students with dyslexia?

Of course, No. 3 is the burning question and the short answer is no. But understanding the “why” and the “what” behind dyslexia-specific fonts helps to put “how effective” in context. We answered these questions by reviewing the information made available on developers’ websites and studies of dyslexia-specific fonts published in peer-reviewed journals (see Table 1).

1. Why might dyslexia-specific fonts matter?

All of this matters because parents and teachers have limited time, and schools have limited budgets and resources. They need accommodations and materials that are effective for students with dyslexia. When parents and teachers spend time and money on ineffective accommodations and materials, they take those resources away from other materials and methods that could be effective. So, if there are effective solutions that are low cost and easy to implement, we need to know about them and support their use.

2. What features of dyslexia-specific fonts make them different from other fonts?

Dyslexia-specific fonts tend to have bolder lines. They tend to have more spacing between the letters within a word. In addition, they tend to increase the spacing between words. Changing existing fonts to reduce the spacing between letters within words is detrimental to all readers. Moreover, research shows that increasing the distance between letters within words without also increasing the space between words results in decreased reading performance for all readers.

Examples:

|

The sun was bright. |

(Arial 12-point font with added spacing) |

|

The sun was bright. |

(Comic Sans MS 12-point font with added spacing) |

|

The sun was bright. |

(OpenDyslexic 12-point font) |

|

The sun was bright. |

(Arial 12-point font no spacing added) |

|

The sun was bright. |

(Comic Sans MS 12-point font no added spacing) |

|

The sun was bright. |

(OpenDyslexic decreased spacing like typical font) |

In addition, most dyslexia fonts were designed to reduce visual resemblance between letters commonly reversed, such as b and d. Moreover, some dyslexia fonts were designed to be visually heavier at the bottom of the letters to give them visual weight to keep them grounded.

These features are intended to address the misconception that individuals with dyslexia see letters backward or jumping around on the page. Although reversals are widely thought to be a hallmark of dyslexia, they are commonly observed in individuals who have not been exposed to a great deal of text, such as young children.

3. Is a dyslexia-specific font an effective accommodation for students with dyslexia?

The findings across the studies we reviewed did not provide evidence that a dyslexia-specific font would be an effective accommodation for students with dyslexia. People with dyslexia can overcome their struggles to read with proper interventions, including explicit instruction, modeling, continued exposure to text, and practice. However, by only changing the font of the text, readers were not able to read words better. Individual readers might prefer a certain font, but based on our review of published research, a particular font does not help individuals with dyslexia read better.

Considering the research on dyslexia fonts, there is limited support for investing time and resources to make these available for students with dyslexia. If a student has a preference, that is one thing. But there is no reason to believe that a dyslexia font is necessary for students with dyslexia to aid them with reading more fluently or accurately. The research on reading fatigue and eye strain is not as robust as the research exploring reading accuracy and fluency. However, there is also no compelling evidence we are aware of to suggest that these fonts are beneficial in these ways either.

Pamela R. Shewalter is a Literacy Studies Ph.D. student at Middle Tennessee State University. She earned her bachelor’s degree in Special Education and an MA in Autism and Applied Behavior Analysis. Her research interests are best practices for interventions and accommodations, generalization of intervention methods, and testing validity for students with reading disabilities.

Timothy N. Odegard, Ph.D., is a professor of psychology and holds the Katherine Davis Murfree Chair of Excellence in Dyslexic Studies at Middle Tennessee State University. He also leads the efforts of the Tennessee Center for the Study and Treatment of Dyslexia. He also serves as Editor-in-Chief of Annals of Dyslexia. Before joining the faculty at MTSU, Tim served on the faculty at the University of Texas Arlington and UT Southwestern Medical School in Dallas. In addition to being a research scientist, Tim is a reading therapist, having completed a two-year dyslexia specialist training program at Texas Scottish Rite Hospital for Children in Dallas during his NIH-funded postdoctoral fellowship.

References

Bachmann, C., & Mengheri, L. (2018). Dyslexia and fonts: Is a specific font useful? Brain Sciences, 8(5), 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci8050089

Duranovic, M., Senka, S., & Babic-Gavric, B. (2018). Influence of increased letter spacing and font type on the reading ability of dyslexic children. Annals of Dyslexia, 68, 218–228. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11881-018-0164-z

Galliussi, J., Perondi, L., Chia, G., Gerbino, W., & Bernardis, P. (2020). Inter-letter spacing, inter-word spacing, and font with dyslexia-friendly features: Testing text readability in people with and without dyslexia. Annals of Dyslexia, 70(1), 141–152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11881-020-00194-x

Kuster, S. M., van Weerdenburg, M., Gompel, M., & Bosman, A. M. (2018). Dyslexie font does not benefit reading in children with or without dyslexia. Annals of Dyslexia, 68, 25–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11881-017-0154-6

Marinus, E., Mostard, M., Segers, E., Schubert, T. M., Madelaine, A., & Wheldall, K. (2016). A special font for people with dyslexia: Does it work and, if so, why? Dyslexia, 22(3), 233–244. https://doi.org/10.1002/dys.1527

Powell, S. L., & Trice, A. D. (2020). The impact of a specialized font on the reading performance of elementary children with reading disability. Contemporary School Psychology, 24, 34–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-019-00225-4

Rello, L., & Baeza-Yates, R. (2013). Good fonts for dyslexia. Assets, 14, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1145/2513383.2513447

Wery, J. J., & Diliberto, J. A. (2017). The effect of a specialized dyslexia font, OpenDyslexic, on reading rate and accuracy. Annals of Dyslexia, 67, 114–127. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11881-016-0127-1

Table 1

Dyslexia and Font

|

Study |

Font Characteristics Manipulated |

Student Characteristics |

Outcome- Accuracy / Rate |

|

Bachmann & Mengheri (2018)

|

EasyReading/ TNR

|

Varied ability

|

Higher for all subjects (due to spacing) |

|

Duranovic et al. (2018) |

Dyslexie font / TNR /Curlz / letter spacing |

Dyslexic; same age; reading matched |

Spacing yes Font no |

|

Galliussi et al. (2020)

|

Verdana/ dyslexia friendly/ letter spacing/ between word spacing |

Dyslexia Control |

No difference in font; reduced with letter spacing; increase with between word spacing |

|

Kuster et al. (2018) |

Dyslexie font/Arial/ TNR |

Dyslexic only Dyslexic & typical |

No difference |

|

Marinus et al. (2016) |

Dyslexie font/ Arial |

At risk |

No difference within word & between word when spacing was added to Arial font

|

|

Powell & Trice (2020) |

Dyslexie font/ Arial & TNR adjusted to comparable size and spacing

|

Students with SLD-reading |

No difference |

|

Rello & Baeza-Yates (2013)

|

OpenDyslexic/ Arial, others |

Dyslexic only |

Font impacts readability; italicized font took longer to read; dyslexia-specific font no difference |

|

Wery & Diliberto (2017) |

OpenDyslexic font/Arial/TNR

|

Dyslexic |

No difference |

TNR = Times New Roman; SLD = Specific Learning Disability

Implementation is Like Instruction

The Summer 2021 issue of Perspectives on Language and Literacy tackles the topic of the implementation of Structured Literacy, and in so doing, taps into multiple core values of the International Dyslexia Association—the why, how, and what we do to help all individuals learn to read. Often, we associate implementation with a top-down administrative plan. But in “Implementing Structured Literacy: Translating the Science of Reading into Practice,” theme editor Dale Webster shares implementation “stories” from individuals with different perspectives—state-level, district-level, and school/classroom-level—to showcase how increased awareness and knowledge on the part of one person or a small group of people can have far-reaching impacts.

These stories remind us that implementation is a lot like instruction; namely, it is a process. The process of effective instruction is one of assessing, teaching, practicing, and reassessing. When done well, the instructional process is iterative rather than linear. Effective implementation is similar. It requires that we meet those doing the implementation where they are, provide opportunities to learn what they need to learn, and adjust the implementation plan based on how the process is working. A common denominator of each step of this process is professional development—knowledge building and on-site support—that accommodates all stakeholders wherever they are in the process to provide whatever they need to contribute to its success.

These stories also remind us that in order to bring about change, each stakeholder has different needs but the same goal—to change outcomes for more students through the knowledge of the Science of Reading and implementation of Structured Literacy.

Effective implementation of Structured Literacy is particularly timely as we focus on identifying, understanding, and treating dyslexia during Dyslexia Awareness Month. Each of these implementation stories tells how individuals applied the Science of Reading to improve the outcome for a greater number of students—the best story of all!

Please take a moment to listen to Dale Webster, Chief Academic Officer for the Consortium on Reaching Excellence in Education (CORE), as he shares some key takeaways from the implementation stories in the Summer 2021 Perspectives issue. Then, join IDA to have access to this issue of Perspectives, and take inspiration from educators whose vision and commitment helped students become competent readers. Have a story of your own? Read the theme editor’s column for how to contribute to the discussion. Joining IDA also gives you access to many other resources to help you with your reading needs. Together we can improve outcomes for many more individuals. Please join us!

Nancy Chapel Eberhardt is currently an educational consultant and author. She has experience as a special education teacher, administrator, and professional development provider. Nancy contributed as author and co-author to the development of the literacy intervention curriculum LANGUAGE! More recently she collaborated with Margie Gillis to develop the Literacy How Professional Learning Series. Nancy is the co-author of Sortegories 3.0, a web-based app that provides practice with decoding, vocabulary, and syntax to improve decoding, reading comprehension, and fluency. She serves as a member of IDA’s Perspectives and The Examiner editorial boards.

Remembering Regina Boulware-Gooden

On September 22, 2021, the International Dyslexia Association lost a dear friend and colleague, Dr. Regina Boulware-Gooden. Regina was a long-time supporter of IDA, and she had recently joined IDA as Accreditation Chair, and later, as Chief Academic Officer. In both roles, Regina made significant and lasting contributions to the organization and the accreditation process for universities and programs committed to preparing teachers to teach Structured Literacy. “Regina was a valued and key member of our team at IDA,” says CEO Sonja Banks. “She worked tirelessly toward our vision of Structured Literacy in every K-3 classroom for every child across the nation and around the world. She will be missed.”

Throughout her career, Regina helped countless individuals as a diagnostician who assessed children with learning disabilities. Prior to joining IDA, Regina also served as VP of academic planning at Neuhaus Education Center, where she worked for 16 years, and as VP of The Reading League Oklahoma. Regina presented both nationally and internationally on the components of reading and identification of learning disabilities.

Regina’s passion, wit, and warm spirit of collaboration will be greatly missed, but her legacy will continue to inspire all of us at IDA who had the privilege and joy of working with her.

For more information on Regina’s life and career, see https://www.oklahoman.com/obituaries/p0149466 for her obituary in The Oklahoman. We would like to thank Regina’s family for selecting IDA as the chosen charity for donations in lieu of flowers. We will utilize these donations to continue her work.